ASC 606. While I think it can be a very useful tool in some situations, like with condominium and homeowner associations, I am not convinced that it will help a reader, an investor, anywhere else. That is because it is almost uniformly built on the concept of management choice – which sadly can lead to poor decisions that ultimately hurt investors.

In a perfect world, I think the concept of ASC 606 is inspiring. Finally, a reader can see what has been committed to and what prices will end up being paid. What a great way to predict a company’s ability to generate future cash flows. But that isn’t what is going to happen. I have seen enough at my end of the spectrum to know that anytime subjective measures are involved, those impacted want the measures skewed in their direction. And something like ASC 606, which almost completely makes determining revenues subjective, simply is going to take this to a new level.

This reminds me of an attest engagement on a contractor. The contractor stated that they had a maintenance contract which runs for 12 months with options to extend an additional 12 months and 6 months. No problem. We though. We asked for the contract, the controller hemmed and hawed. Why? She put the information into the disclosure so there must be a basis for its inclusion.

Apparently not. It seems that the customer is not so thrilled and has expressed that they won’t extend the contract. But there is a catch.

The customer is also the ultimate customer on several other contracts. It seems that the customer accounts for about 60% of the revenues for this company and when this contract goes, there is about a 99.8% chance that the other contracts are not renewed and new contracts won’t be awarded.

This all came to a head when we questioned the fade, or loss of gross profit, over contracts. Long-term contracts are handled on the guesstimate method. We use the “objective” measure of actual cost incurred in relationship to the guess of total estimated costs. The total estimated cost is management’s choice, its illusion, which drives not only gross profit recognized but also the percentage of completion.

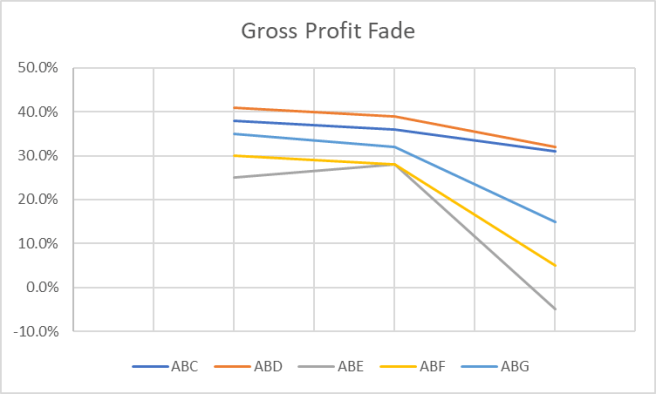

We identified a problem. The fade, or the loss of gross profit over time, on contracts was starting to become noticeable. The graph shows what we noticed:

The gross profit percentage ends up remarkably lower over time. There is really only one reason for this, the inability to estimate accurately. Notice that all fade is in excess of 5 basis points, the smallest fade being 7 points on project ABC. If this were a $10,000 project, that wouldn’t be a big issue but it is their second largest contract. And worse, you can see that on one job they estimated an increase in gross profit in year two only to have it plunge to a net contract loss of 5%.

I know I know, the point.

The problem is that they estimated their new contract, the one likely not to get extended at 45% gross profit. The trend though, is clear: Gross profit fades lower consistently over time. The trend indicates to us that the project will end up at 30% overall. The project AAA is recorded at 5% complete which means the company has recorded over $100K of gross profit. The trend says that, at best, they have earned $67K.

But wait, there’s more.

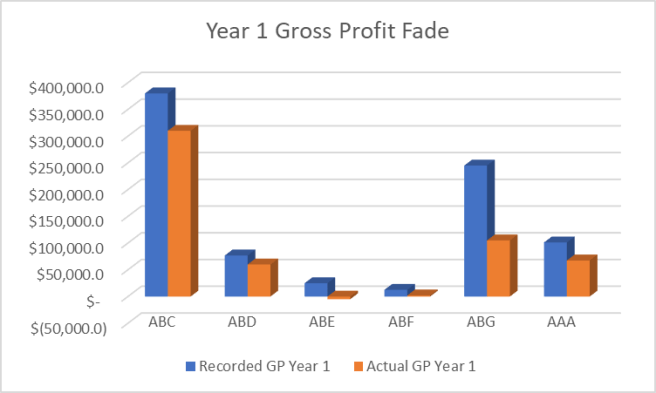

Since the original estimated cost in year one is too low, this changes the percentage of completion. Not a lot, but enough. The true fade, after revising the percentage of completion is

Huge. So huge, in fact, that it can’t be ignored. It totals out to about $375K of gross profit incorrectly recognized in earlier years.

Of course, our concern is not really those older contracts, it is the new one, the one which is likely not to be extended. It is our concern that current gross profit is overstated by about $50K AND it is likely that this contract won’t be reupped and that there will be no future contracts with this customer.

With the loss of this customer, revenues will drop 50%. Given the fade problem from poor estimates, the company has not had the gross profit it envisioned on these projects which has forced it to borrow heavily to meet its operating needs during the end phase of these projects. The borrowing, by the way, is from both the bank and the new projects with higher initial gross profit that will ultimately fade away.

Since we are independent CPA’s attesting to the financial statements, we are held to the standard that we think the company in question can continue as a going concern for at least one year from the date of our report. We ran several different scenarios, none of which succeed in changing the trajectory.

I would like to say there was a happy ending. I guess in a way there was. Management, the sole owner, decided to terminate our engagement. The next year, the owner filed for bankruptcy. The bank never got is independent accountants’ report by the way. They didn’t call the loan and ended up with over a $500K loss due to the reorganization.

It is tempting to believe that management wants accuracy and objectivity in its reports. But as with estimated costs to complete, ASC 606 is open to management’s very subjective and capitalistic approach. Management is responsible for

- determining what makes up a contract with a customer

- selecting at least one (and possibly only one) performance obligation

- Allocating the contract price over the performance obligations

- Determining when the performance obligation is complete so that the price can be recognized

These all have similar requirements – management’s ability to use good judgment. And much like with contract estimates under old GAAP, it will be well-nigh impossible for an independent CPA to challenge management’s assertions, until it is too late.